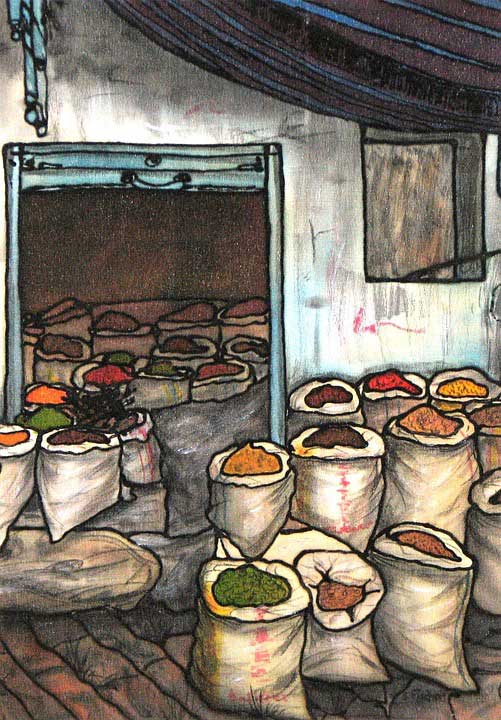

In a misty morning market in southern India, the air hangs heavy with the scent of damp earth and sun-warmed root. A knobby rhizome, freshly unearthed, is split open, revealing a glowing core of saffron-orange flesh whose pungent, slightly peppery aroma rises into the air like incense. That scent, vibrant and earthy, whispers of ancient soils, centuries of cultivation, and generations of cooks. It is the spirit of turmeric, and in that moment, you feel yourself stepping into a story that spans millennia, continents, and cultures.

Turmeric, or Curcuma longa, is native to tropical southern Asia, especially India and Indonesia, where it grows as a perennial herb in the ginger family. The vivid yellow-orange heart of the plant, its rhizome, is dug from the rich, monsoon-softened soil, boiled, dried, and ground into the golden powder that millions sprinkle daily into their food. The spice’s botanical roots stretch deep: it thrives in warm, humid climates, relying on between 20 and 30 degrees Celsius and generous rainfall to produce its knobby underground stems.

The history of turmeric is as rich as its color. Humans have cherished it for perhaps 4,000 to 6,000 years, first in ancient Indian cultures. Vedic texts mention its use in traditional rituals, while Ayurveda and Siddha medicine employed it for healing everything from digestive troubles to wounds. Turmeric was not just a medicinal root; it was a symbol. In India, brides and grooms have long used turmeric paste in wedding ceremonies, believing it brings purity, prosperity, and a radiant glow. Its bright hue also lent itself to more mundane yet profound roles: dyeing garments, coloring oils, and even in art.

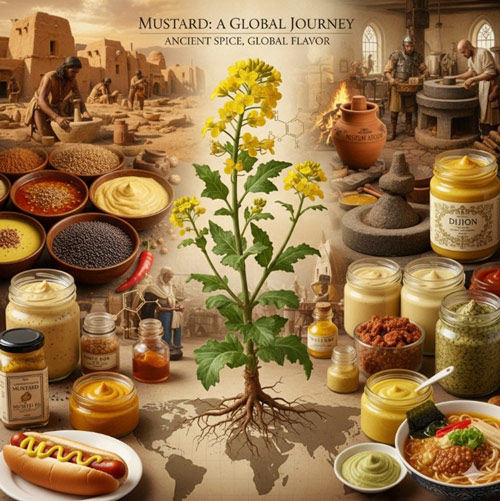

Over centuries, the golden spice traveled beyond its birthplace. By around 700 CE, traders carried turmeric along the Silk Road to the Middle East. From there, it reached East Africa by around 800 CE and West Africa by 1200 CE. Arab merchants introduced it to Europe, and medieval Europeans called it ‘Indian saffron’ thanks to its brilliant color and aromatic warmth. Great explorers too took notice: Marco Polo, in his 13th-century travels, described a plant in China whose color and scent rivaled pure saffron.

But turmeric is more than legend and trade: it carries profound cultural weight. In Hindu and Buddhist traditions, its golden powder represents sanctity, purity, and fertility. Across Southeast Asia, especially in Austronesian societies, turmeric became central to rituals, body painting, and cloth dyeing, its name embedded in many early languages as a symbol of color itself.

Turmeric in kitchens

In kitchens around the world, it has shaped tastes. In Indian cuisine it is one of the first spices to be tempered in hot oil, releasing its warmth into dals, curries, rice pilafs, and chutneys. Its cheerful golden color brightens mustard, butter, and cheeses, while ground turmeric finds its way into pickles, relishes, and spiced pastries. In Southeast Asia, turmeric flavors soups and stews, mingling with coconut milk and lemongrass. In the Middle East and Africa, it is prized for its dyeing power, used in textiles and cosmetics just as much as in food. Its deep hue and earthy taste connect humble village kitchens to high-end gastronomic plates.

Beyond its culinary role, turmeric has become the darling of modern science. Its principal active compound, curcumin, has been studied extensively for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and even anticancer properties. Researchers now use turmeric extracts in supplements, cosmetics, and health-care products across the globe. In Ayurvedic tradition, turmeric eased skin disorders, aided digestion, and helped respiratory ailments; today, clinical research confirms many of those effects, linking curcumin to benefits in heart health, joint pain, and chronic inflammation.

An expert in medicinal botanicals might reflect: ‘When I hold a piece of fresh turmeric root, I am touching both ancient wisdom and modern science. Its color tells a story of tradition, and its chemistry whispers of possibility.’ Such a voice bridges two worlds: one rooted in ritual, the other in laboratory.

Even in agricultural fields, turmeric’s journey continues. India remains by far its largest producer, responsible for around 80 percent of global cultivation. But that dominance comes with challenges. In recent years, farmers have struggled to meet rising demand for high-curcumin turmeric, which fetches premium prices in Western markets. This quest for potency echoes the spice’s long passage from folk medicine to functional food, and from sacred paste to commercial extract.

In modern kitchens, turmeric also finds new homes. Craftsmen mix it into golden lattes, smoothies, and wellness teas. Chefs experiment with turmeric-infused oils, dressings, even desserts: panna cotta dusted with turmeric, or chocolate lightly tinged with it. These innovations show how a spice once confined to curry pots has become a global muse.

Scientific research is still chasing turmeric’s full promise. Studies continue to explore curcumin’s role in neuroprotection, metabolic support, and cancer prevention. Meanwhile, some researchers warn of its low bioavailability: curcumin does not absorb easily into the bloodstream unless paired with black pepper or fat, a lesson traditional cooks may have intuited long ago.

Through all these changes, turmeric retains its soul. It continues to infuse spiritual ceremonies in India, where a pinch of yellow dust still smudges foreheads and garlands. It lingers in the memory of families, in the taste of grandmothers’ stews, in the dance of vibrant markets. Its journey has been one of devotion, trade, healing, and discovery.

When you pause to stir turmeric into your next meal or sip golden-hued tea, you are touching more than flavor. You are reaching across thousands of years to a world where spice, ritual, medicine, and art all blended in a single root. In its buttery glow, you sense an unbroken thread: from ancient Vedic poets to modern scientists, from temple altars to urban cafés. Turmeric’s golden journey reminds us that even the humblest spice can carry the weight of history, and the promise of tomorrow.