A Small Pepper With a Big Culinary Legacy

In the world of Spanish spices, some ingredients are quiet heroes—less globally famous than saffron or smoked paprika, yet essential to regional culinary identity. The ñora pepper is one such gem. Small, round, and deep red, ñoras are sun-dried peppers traditionally grown in the Mediterranean regions of Murcia, Alicante, and parts of Valencia. Despite their modest appearance, they carry a rich, fruity sweetness and an aroma that instantly evokes the warmth of Spain’s southeastern coast.

In Spanish cooking, particularly in Levantine cuisine, ñora peppers are the foundation of many iconic dishes—rice preparations, stews, and especially sauces such as the famous romesco. They are beloved not for spiciness (since ñoras contain almost no heat), but for their sweetness, depth, and umami quality. This article explores the unique taste of ñora peppers, their culinary uses, their rich cultural history, and why they remain a key staple in Mediterranean kitchens.

Flavor Profile: Sweet, Fruity, Aromatic, and Completely Mild

The flavor of ñora peppers is distinct and unmistakable. Unlike fiery Spanish peppers such as pimentón picante, the ñora is all charm and sweetness.

Key Characteristics of Ñora Peppers

- Naturally sweet, with a fruity intensity reminiscent of sun-dried tomatoes

- Completely mild, containing virtually no capsaicin

- Soft, smoky undertones, not from smoking but from sun-drying

- Umami-rich, adding depth without overpowering other ingredients

- Aroma of dried fruit, with a slightly caramelized fragrance

Because of their complexity and lack of heat, ñoras are favored by cooks who want gentle sweetness and richness without spiciness. This makes them incredibly versatile in stews and sauces, acting as a harmonious flavor base that ties ingredients together.

How to Use Ñora Peppers: A Mediterranean Essential

Unlike powdered spices, ñora peppers are usually sold whole and dried. Because their skin is tough, they are rarely used directly in dishes without preparation. Instead, they are rehydrated and the pulp is extracted.

1. Rehydrating Ñora Peppers: Step-by-Step

To prepare ñoras properly:

- Remove the stem and shake out the seeds.

- Soak the peppers in warm water for 15–20 minutes.

- Once soft, split them open.

- Scrape out the soft, aromatic flesh with a spoon.

This pulp—deep red and highly fragrant—is the true treasure of the ñora.

2. Ñoras in Rice Dishes (Arroces)

In southeastern Spain, ñora pepper pulp is a foundational element in many rice dishes, particularly:

- Arroz a banda

- Arroz con costra

- Fideuà

- Traditional Alicante-style paellas

The pepper contributes sweetness, color, and a savory backbone that enhances seafood, meats, and vegetables.

3. Romesco Sauce: A Spanish Icon Powered by Ñoras

Perhaps the most famous use of ñoras is in romesco sauce, a Catalan classic. Traditionally eaten with:

- Grilled calçots (sweet onions)

- Roasted vegetables

- Fish and seafood

- Grilled meats

Romesco blends ñora pulp with almonds, garlic, olive oil, tomatoes, and vinegar. The result is a thick, smoky-sweet sauce that is one of the most beloved condiments in Spanish cuisine. Without ñora peppers, authentic romesco loses its characteristic depth and Mediterranean sweetness.

4. Stews, Soups, and Fish Preparations

Ñoras are widely used in slow-cooked dishes, such as:

- Fish stews

- Vegetable guisos

- Meat-based casseroles

- Brothy seafood soups

They add richness, roundness, and subtle fruitiness that elevates even simple recipes.

5. Homemade Sofritos and Seasoning Bases

Ñora pulp is often added to Spanish sofrito—Spain’s version of a flavor base similar to French mirepoix or Italian soffritto. A classic sofrito of onions, garlic, tomatoes, and ñora pulp forms the backbone of countless Mediterranean dishes.

The History and Cultural Significance of Ñora Peppers

The ñora pepper has deep roots in Spanish agriculture and cuisine. Originally introduced from the Americas in the 16th century—like most peppers—it adapted exceptionally well to the warm, sunny climate of southeastern Spain.

1. The Origin of the Name “Ñora”

The name ñora is believed to come from the small Murcian coastal village of La Ñora, where the pepper was widely cultivated and used in traditional cooking. Over time, the pepper took on the name of the region that made it famous.

2. A Tradition of Sun-Drying

Unlike smoked paprika, which is dried over wood fires, ñoras are dried naturally under the Mediterranean sun. This slow dehydration method concentrates their sugars and enhances their fruity aroma. Sun-drying has been a traditional preservation method in the region for centuries.

3. A Cultural Symbol of Murcia and Valencia

Today, the ñora pepper is not just an ingredient—it is a point of cultural pride. Many regional dishes simply cannot be recreated without it. In Murcia, for example, ñoras are used to make pimentón murciano, a paprika that is sweeter and more tomato-like than smoked paprika.

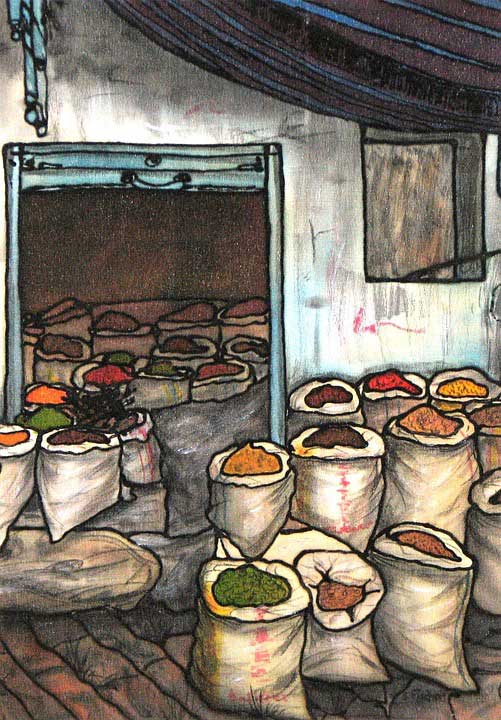

The pepper also plays a role in local festivals, markets, and artisanal traditions, where dried ñoras are often sold in decorative strings.

Why Ñora Peppers Matter in Modern Cooking

In contemporary cuisine, chefs increasingly value ingredients with distinct terroir and cultural identity. Ñora peppers offer:

- Authenticity in Mediterranean and Spanish dishes

- Natural sweetness without sugar

- Rich umami, ideal for vegetarian and vegan cooking

- Visual appeal, thanks to their deep red color

- Versatility, blending beautifully with seafood, meats, vegetables, and grains

As global interest in Spanish cuisine grows, ñoras are becoming more widely available in gourmet stores and online spice shops.

Conclusion: A Sweet, Fruity Treasure Worth Knowing

The ñora pepper may be small, but its impact on Spanish cuisine is enormous. From the bold romesco sauces of Catalonia to the fragrant rice dishes of Alicante and Murcia, ñoras bring sweetness, depth, and Mediterranean identity to every recipe they touch. Their mild, fruity flavor makes them accessible to all palates, while their rich history adds cultural significance to every bite.

For cooks looking to explore the authentic tastes of Spain—or for anyone searching for a versatile, naturally sweet pepper to elevate their dishes—the ñora is a spice cabinet essential.

Other Spanish Typical Spices:

– Saffron