Few foods are as universally loved—and as widely interpreted—as curry. Found in homes and restaurants from India to Japan, Thailand to Jamaica, and Britain to South Africa, curry is not a single dish but a world of flavors, histories, and traditions. Its story spans continents, colonial encounters, spice routes, migrations, and creative reinvention. For anyone curious about the history of curry, this global journey reveals how deeply interconnected food and culture can be. And whether simmered slowly on a family stove or ordered from a bustling street market, curry remains one of the world’s most comforting and expressive culinary creations.

A Brief History of Curry

The history of curry begins with the ancient Tamil word kari, meaning “spiced sauce,” but the culinary concept we now associate with curry is thousands of years old..

In the Indus Valley civilization—one of the world’s earliest urban cultures—archaeologists have uncovered evidence of turmeric, ginger, and garlic in ancient cooking pots, suggesting that proto-curry mixtures may date back more than 4,000 years. Indian cuisine continued to evolve under diverse regional kingdoms, each developing its own masalas (spice blends) tailored to climate, agriculture, and culture.

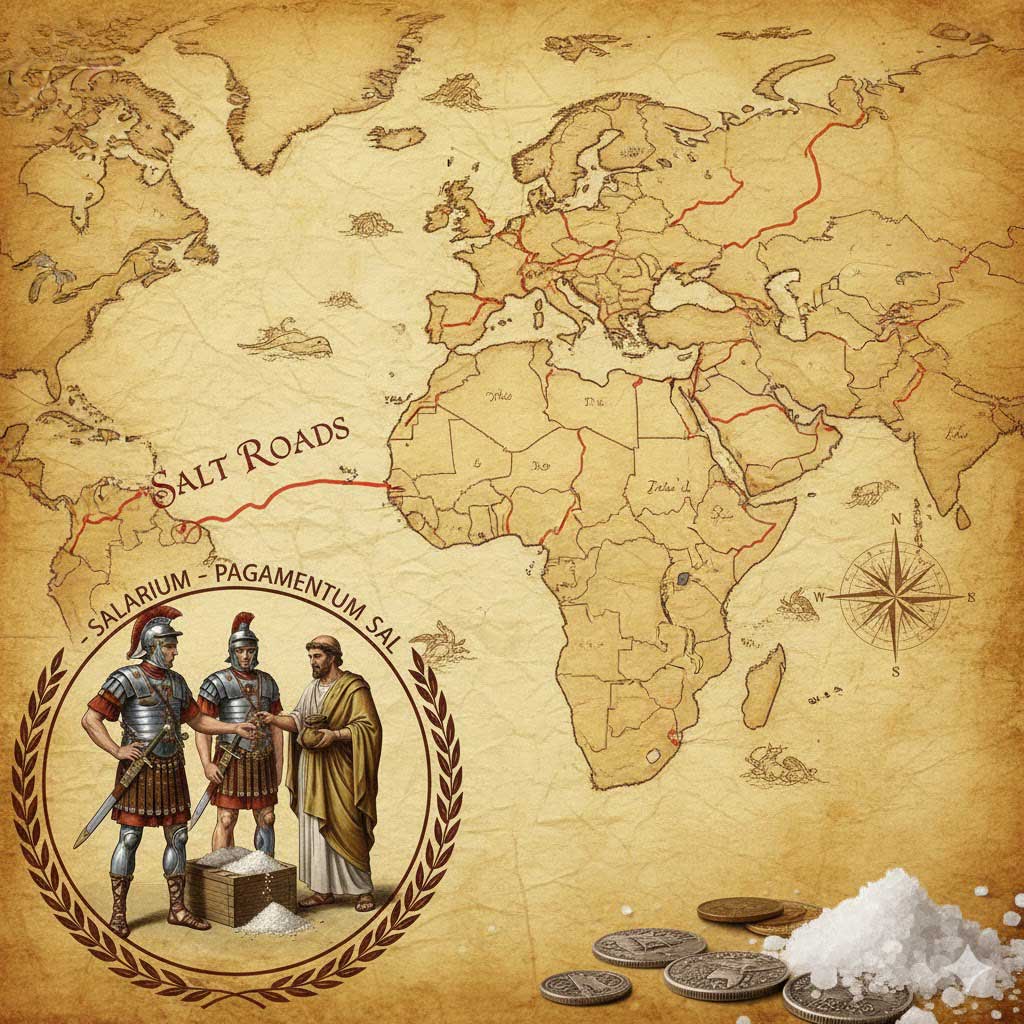

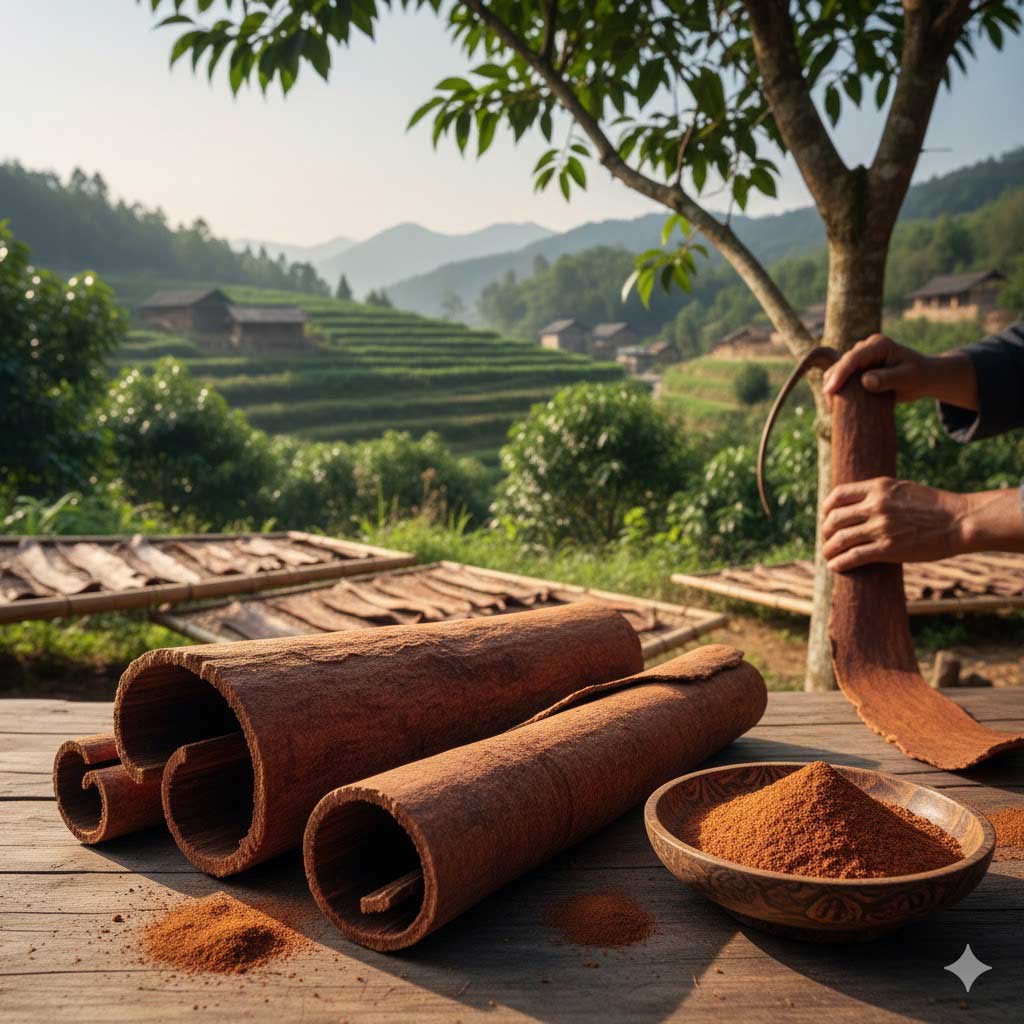

The global rise of curry began with the spice trade. Arab merchants carried Indian spices westward, and by the Middle Ages, pepper, cinnamon, and cardamom were prized luxuries in Europe. Later, during the period of British colonial rule, curry became a bridge between cultures. British officers who developed a taste for Indian cuisine tried to recreate it back home, leading to the first English “curry powder,” an approximation of Indian masalas designed for Victorian kitchens.

As global migration increased, the concept of curry traveled with people:

- Indian laborers brought curry traditions to the Caribbean, giving birth to Jamaican curry goat and Trinidadian doubles.

- Japanese naval officers encountered British-style curry and transformed it into the mild, comforting kare raisu beloved across Japan today.

- Thai cooks incorporated local herbs like lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir lime into vibrant coconut-based curries.

Today, curry is less a recipe than a culinary conversation—one that adapts, evolves, and absorbs local identity wherever it travels.

Anecdotes & Cultural Flavor

Few foods inspire as many personal stories as curry. In many cultures, curry isn’t just a dish; it’s an expression of identity and memory.

The Family Masala

In many Indian households, spice blends are guarded like family heirlooms. A grandmother’s masala recipe might be written down (rarely) or passed on by smell and intuition. Some families roast their spices before grinding; others sun-dry them on terraces, infusing them with the warmth of the afternoon. The taste of curry, in these homes, is the taste of lineage.

An old joke in North India goes: “If you want to marry into a family, learn their garam masala first.” Whether true or not, it reflects how deeply curry is tied to domestic tradition.

Curry and Colonial Curiosity

A British anecdote tells of an 18th-century dinner guest who asked for “that excellent spicy Indian ragout” again. Unable to recall the dish’s Tamil name, the host simply called it “curry.” The term stuck, much to the amusement—and occasional annoyance—of Indians who know that every regional dish has its own name, from vindaloo to korma, saag, chettinad, or kari kuzhambu.

The Comfort of Kare

In Japan, curry is as beloved as ramen or sushi. Ask a Japanese college student what they ate during exam season, and many will recall giant pots of homemade curry simmering for days, growing richer with every serving. It is affectionately called “the national comfort food.”

Three Delicious Curry Recipes to Try at Home

Here are three diverse recipes that showcase curry’s global personality.

1. Classic Indian Chicken Curry (North Indian Style)

Ingredients:

- 1.5 lbs chicken pieces

- 2 onions, finely chopped

- 3 tomatoes, blended or chopped

- 4 cloves garlic, minced

- 1-inch ginger, minced

- 2–3 tbsp oil

- 1 bay leaf

- 1 tsp cumin seeds

- 1 tsp turmeric

- 2 tsp coriander powder

- 1 tsp garam masala

- 1 tsp red chili powder

- Salt to taste

- Fresh cilantro for garnish

Instructions:

- Heat oil and add cumin seeds and bay leaf until fragrant.

- Add onions and cook until golden brown.

- Stir in garlic and ginger; sauté for one minute.

- Add tomatoes and spices; cook until oil separates from the masala.

- Add chicken pieces and coat well with the mixture.

- Add 1 cup water and simmer for 25–30 minutes.

- Garnish with cilantro and serve with rice or flatbread.

This curry is deeply aromatic, richly spiced, and endlessly adaptable—just like the regions that inspired it.

2. Thai Green Curry

Ingredients:

- 2 tbsp green curry paste

- 1 can (13.5 oz) coconut milk

- 1 lb chicken or tofu

- 1 cup Thai eggplant or zucchini

- 1 red bell pepper

- 1 tbsp fish sauce (or soy for vegan)

- 1 tbsp brown sugar

- Handful of Thai basil

- Kaffir lime leaves (optional)

Instructions:

- Heat a spoonful of coconut milk until it bubbles and releases aroma.

- Stir in the green curry paste and cook for 1–2 minutes.

- Add the remaining coconut milk, chicken/tofu, and vegetables.

- Add fish sauce, sugar, and lime leaves.

- Simmer on low for 15 minutes, until fragrant and silky.

- Finish with Thai basil.

Thai curry is all about balance: creamy, spicy, fragrant, and fresh.

3. Japanese Curry Rice (Kare Raisu)

Ingredients:

- 1 lb beef, chicken, or vegetables

- 2 onions

- 2 carrots

- 2 potatoes

- 1 apple, grated

- 3 cups water

- 1 block Japanese curry roux

- Cooked rice

Instructions:

- Sauté onions until caramelized.

- Add meat and vegetables; lightly brown.

- Pour in water and simmer until everything softens.

- Add grated apple for sweetness.

- Stir in curry roux until thick and glossy.

- Serve over steaming rice.

This curry is mild, comforting, and subtly sweet—perfect for cozy evenings.

Check also this great recipe of delicious Autumn Chickpea Curry!

Curry’s Ever-Expanding Story

The history of curry shows that it is far more than a recipe—it is a symbol of cultural exchange, adaptation, and memory. It’s eaten during celebrations, shared among friends, reinvented by chefs, and passed down through generations. Its ability to absorb local ingredients, preferences, and stories makes it one of the world’s most adaptable foods.

Whether fiery and complex, creamy and mild, or bright with fresh herbs, curry continues to evolve. Every pot tells a story—and adds a new chapter to the history of curry.