What Is Cinnamon? A Warm and Ancient Spice

Discover Cinnamon history : Cinnamon is one of the world’s most cherished spices, known for its unmistakable warmth and sweet aroma. Made from the inner bark of Cinnamomum trees, it has been used for thousands of years in cooking, medicine, and ritual practices.

Cinnamon remains a staple in cuisines across the globe thanks to its versatility—equally at home in baked goods, drinks, stews, and spice blends.

A Brief Cinnamon History

Cinnamon History : Ancient Civilizations

Cinnamon history stretches back over 4,000 years. Ancient Egyptians valued it as highly as gold, using it in:

- Perfumes

- Religious rituals

- Embalming practices

Its rarity made it a luxury commodity throughout the ancient Mediterranean.

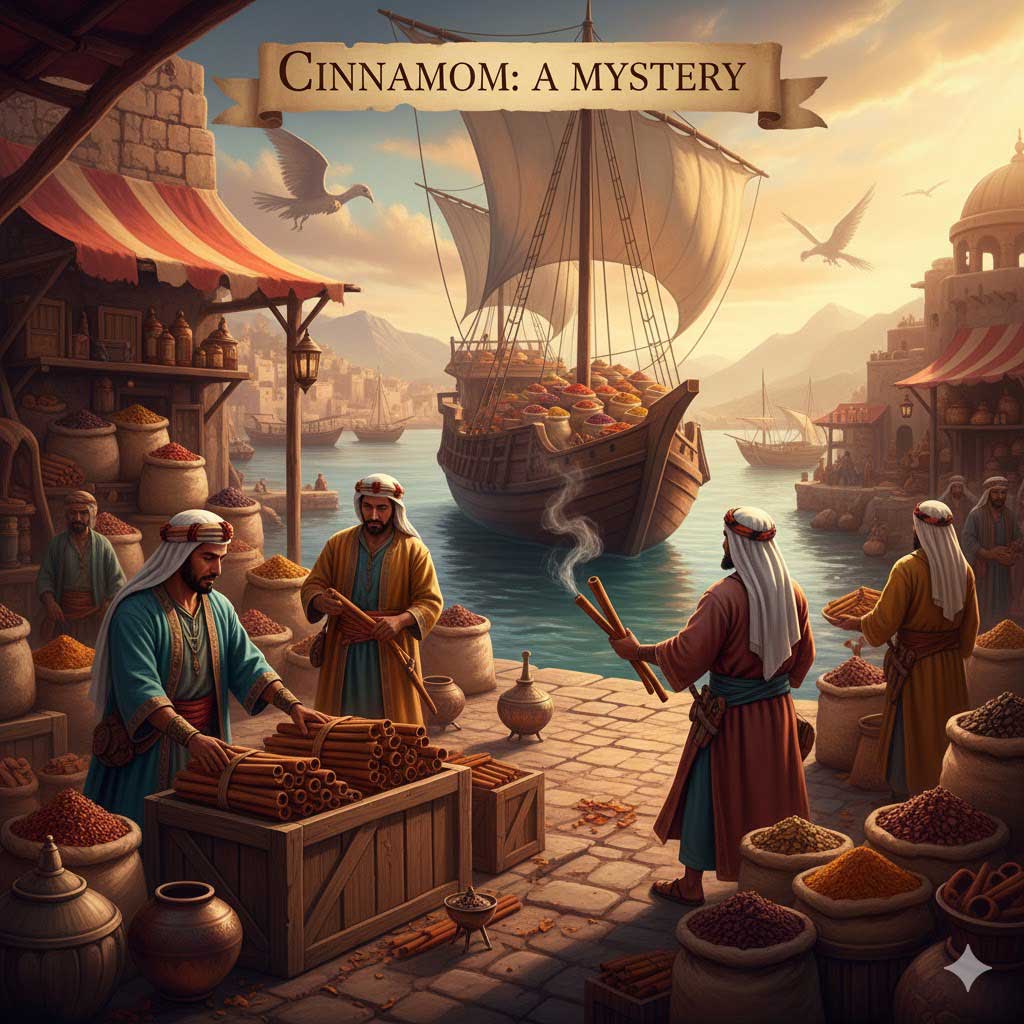

The Mystery of the Cinnamon Bird

Arab spice traders once controlled cinnamon’s supply and crafted fantastic legends to protect their monopoly.

One famous tale claimed cinnamon was harvested from the nests of giant mythical birds perched on high cliffs. Merchants supposedly used heavy meat to break the nests, allowing cinnamon sticks to fall. This myth helped maintain cinnamon’s status as a precious, nearly unreachable spice.

Cinnamon in Greek and Roman Culture

The Greeks and Romans adored cinnamon for flavoring wine, medicinal infusions, and ceremonial uses. In one dramatic anecdote, Emperor Nero reportedly burned a year’s supply of cinnamon at his wife’s funeral.

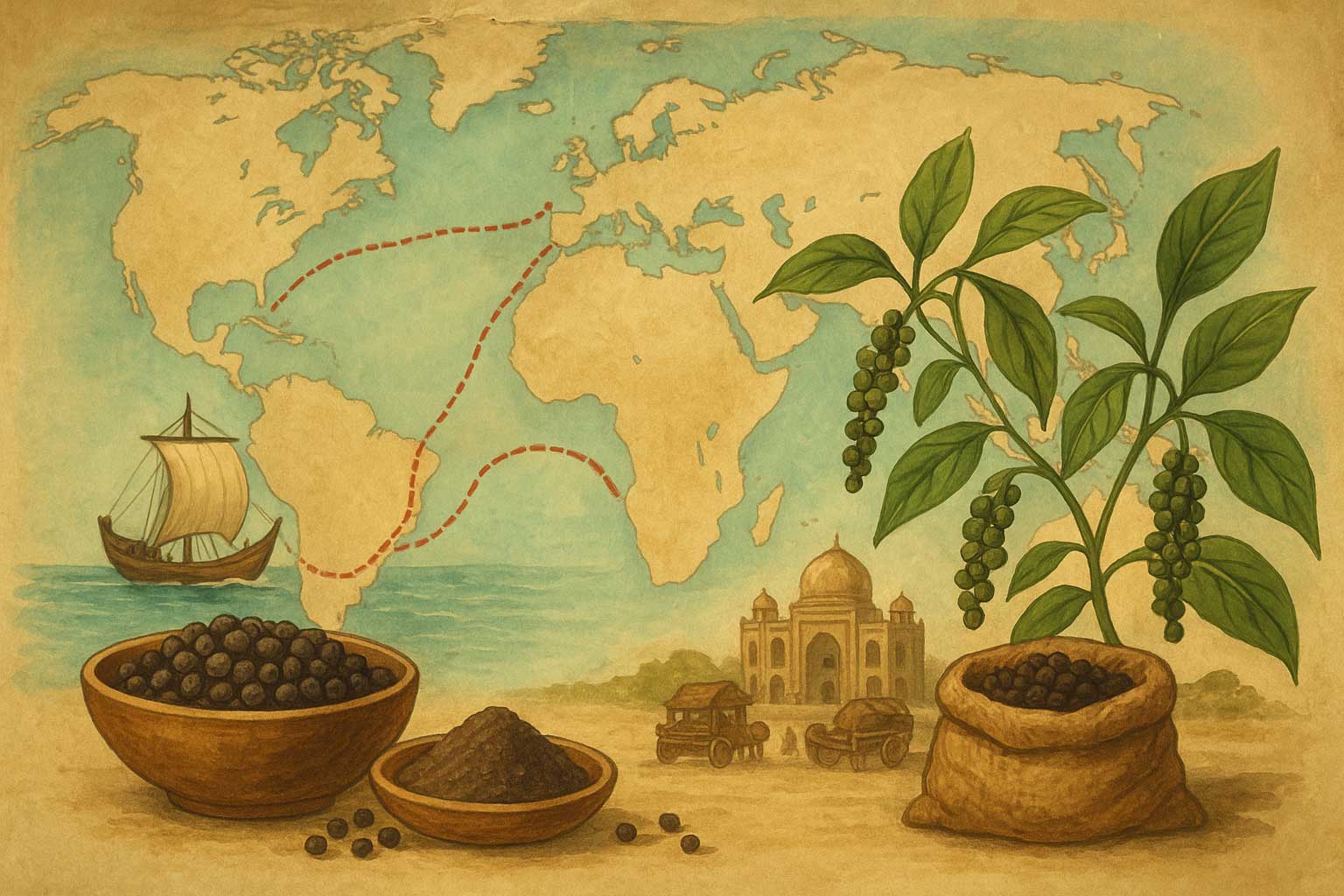

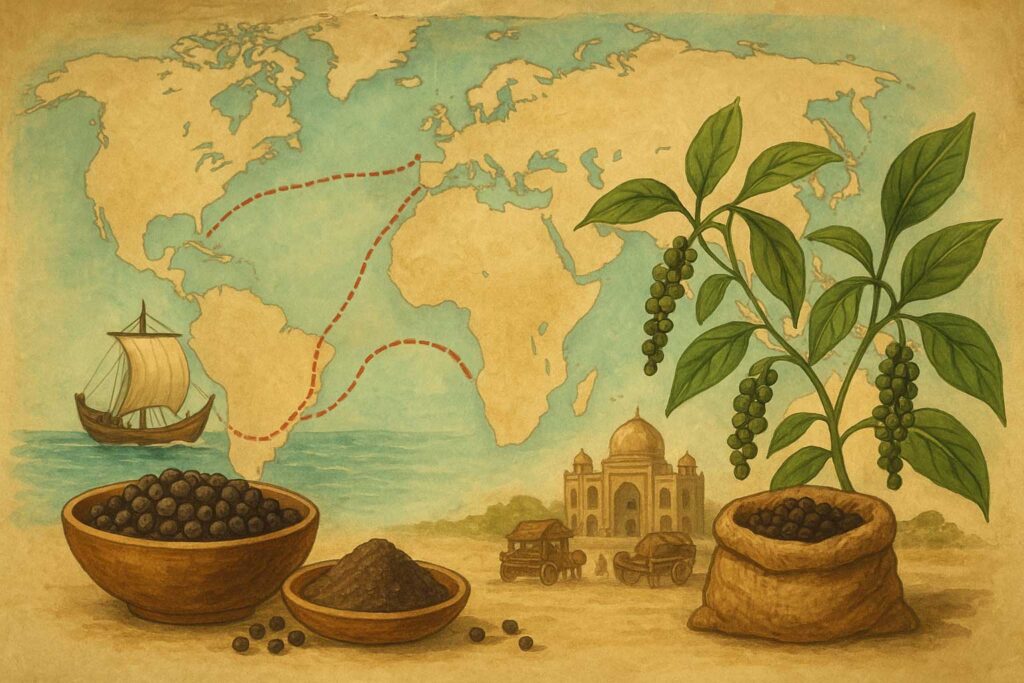

Cinnamon and the Age of Exploration

During the 15th–17th centuries, European empires battled for control of Sri Lanka (Ceylon), the top cinnamon-producing region. Cinnamon fueled major trade routes and colonial expansion—demonstrating how impactful this humble spice has been in shaping world history.

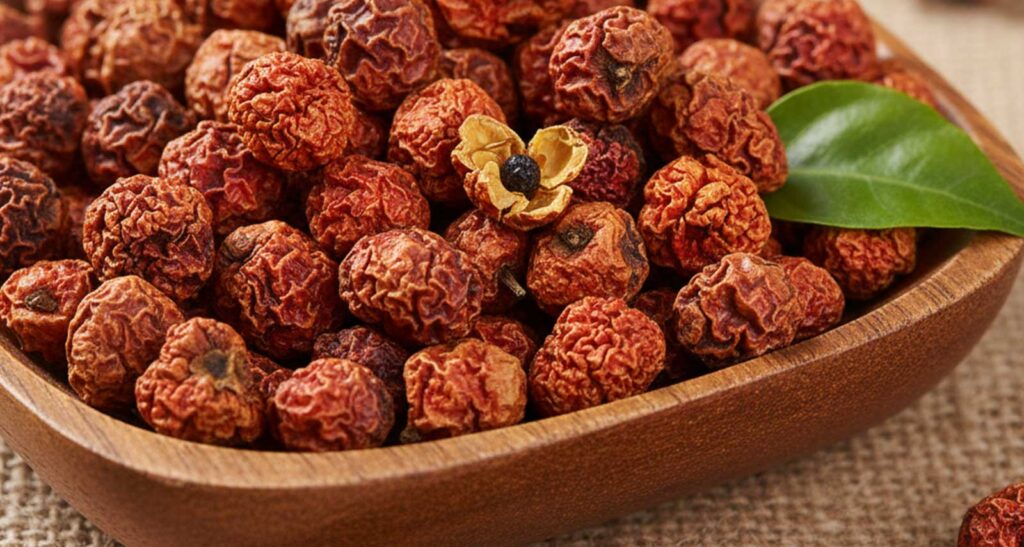

Ceylon vs. Cassia: Types of Cinnamon

1. Ceylon Cinnamon (“True Cinnamon”)

- Grown mainly in Sri Lanka

- Light, sweet, delicate flavor

- Thin, layered, flaky sticks

- Preferred for desserts, teas, and subtle dishes

2. Cassia Cinnamon

- Common in supermarkets

- Bold, strong flavor

- Thick, hard sticks

- Ideal for savory dishes, stews, and spice rubs

See also this post.

Cultural Anecdotes and Symbolism of Cinnamon

Cinnamon’s symbolism varies across cultures:

- Middle Eastern traditions: Cinnamon tea signals welcome and hospitality.

- Ancient rituals: It appears in biblical anointing oils and sacred blends.

- Modern aromatherapy: Cinnamon is associated with warmth, comfort, and stress relief.

Its enduring presence in folklore and medicine gives cinnamon a magical, almost nostalgic appeal.

How to Use Cinnamon: Recipes and Ideas

1. Easy Cinnamon Honey Butter

Perfect for breakfast or holiday spreads.

Ingredients:

½ cup unsalted butter, 2 tbsp honey, 1 tsp cinnamon

Instructions:

Mix until smooth. Add a pinch of salt for balance.

2. Cinnamon Chickpea Stew

A cozy, aromatic dish with Middle Eastern spices.

Ingredients:

Onion, garlic, cinnamon, cumin, paprika, tomatoes, chickpeas, broth

Instructions:

Sauté aromatics → add spices → simmer 20 minutes.

3. Classic Cinnamon Swirl Bread

A cozy weekend baking project.

Key Steps:

- Make a simple enriched dough using flour, yeast, milk, butter, and sugar.

- Roll out the dough and spread a mixture of cinnamon and sugar across the surface.

- Roll tightly, place in a loaf pan, and let rise again.

- Bake until golden and fragrant.

The result is a soft, sweet loaf perfect for toast or French toast.

4. Cinnamon-Steeped Hot Chocolate

Add depth to your winter beverage by warming milk with a cinnamon stick before mixing in cocoa and sugar. The infusion turns a simple hot chocolate into something special.

A Spice That Endures

Cinnamon’s enduring popularity isn’t simply due to its flavor. It’s a spice with stories—of ancient rituals, mythical birds, global trade, and shared meals across cultures. Its aroma evokes warmth and familiarity, while its history reminds us how deeply connected the world has always been through food.

Whether you swirl it into a dessert, brew it into a drink, or sprinkle it onto something savory, cinnamon continues to weave itself into our kitchens and our lives, just as it has for thousands of years.