Welcome, fellow culinary adventurers, to a deep dive into the tiny, aromatic, and surprisingly dramatic world of spices! We all have them, tucked away in those little jars, silently judging our cooking skills (or lack thereof). But have you ever truly listened to them? Have you considered their intricate social hierarchies, their petty rivalries, and their unfulfilled aspirations? No? Well, settle in, because it’s time to pull back the curtain on the secret lives of your kitchen’s most flamboyant residents.

First, let’s address the undeniable celebrities of the spice rack: Turmeric, Paprika, and the ever-so-fragrant Cinnamon.

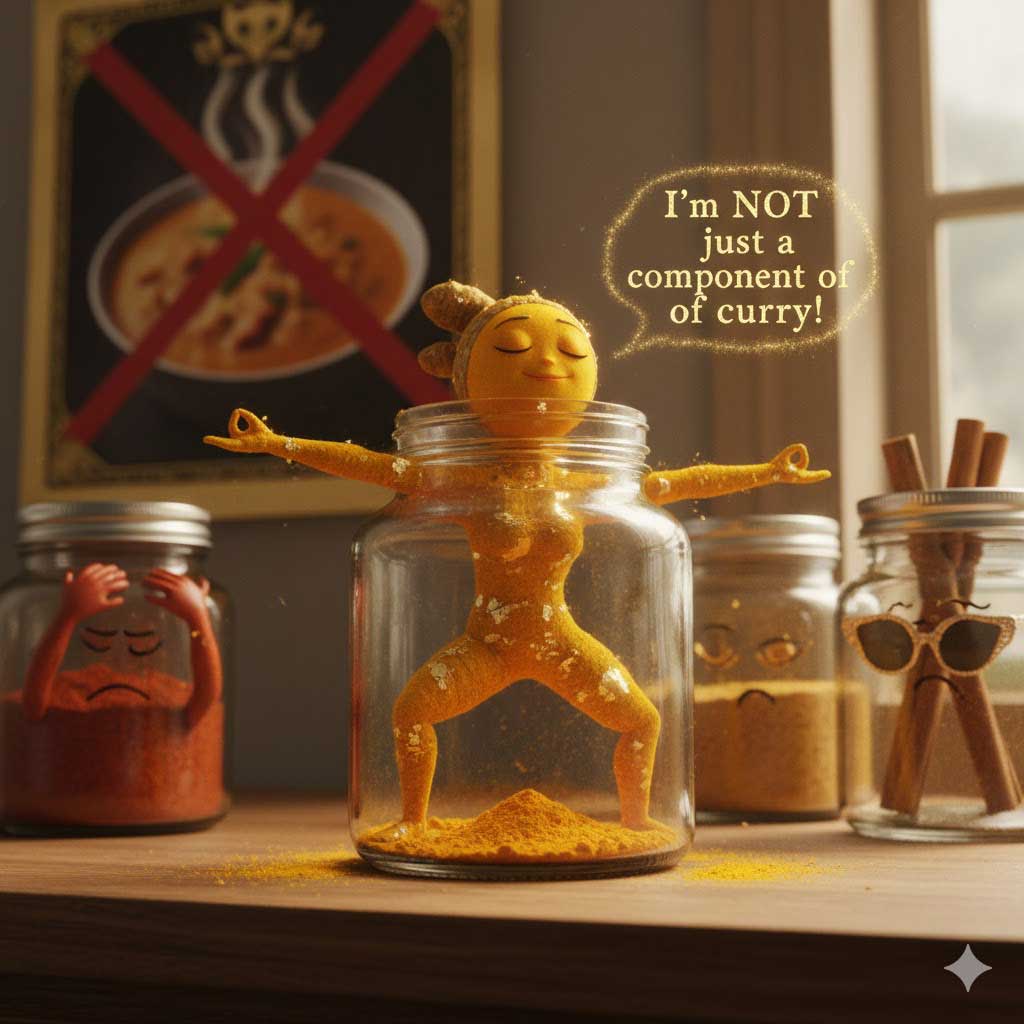

Turmeric: Ah, Turmeric. The wellness guru of the group. Always talking about its “anti-inflammatory properties” and its “ancient roots.” You just know it’s constantly doing yoga poses in its jar and lecturing the other spices about the benefits of a “golden latte.” It’s incredibly popular, but sometimes you just want to tell it to chill out and stop trying to heal everything. Its biggest insecurity? Being mistaken for curry powder. “I’m NOT just a component of curry!” it shrieks, whenever someone mentions Indian food. “I have my own distinct identity!” We get it, Turmeric, you’re special.

Chapter 2: The A-Listers (Continued): Paprika, the Brooding Artist, and Cinnamon, the Undeniable Diva (Approx. 280 words)

Following our wellness-obsessed Turmeric, we delve deeper into the celebrity row of the spice rack.

Paprika: Paprika is the quiet, brooding artist of the rack. It comes in many shades – sweet, smoked, hot – each a different artistic phase. Sweet Paprika is the gentle soul, always trying to bring warmth to a dish without offending anyone. Smoked Paprika, on the other hand, is the edgy one, smelling faintly of campfires and forbidden secrets. Hot Paprika is just… angry. All the time. Its internal monologue is probably just a series of “Hmph!” and “Feel my burn!” They all secretly resent being relegated to just a garnish for deviled eggs. “Our depths go beyond mere aesthetics!” they whisper dramatically.

Cinnamon: And then there’s Cinnamon, the undeniable diva. It knows it smells amazing, and it flaunts it. Always dressed to impress, often found draped over apple pies or stirring up controversy in a chai latte. Cinnamon is the one who insists on being called by its full name, “Ceylon Cinnamon,” if it’s the good stuff, or dramatically rolls its eyes if it’s merely “Cassia.” It’s secretly terrified of being replaced by “Pumpkin Spice Blend” during autumn, viewing it as an uncultured imposter. “Honestly,” it sighs, “the sheer lack of discernment!”

These three often form a dramatic trio, constantly vying for the spotlight in your next culinary creation. Turmeric will be performing its sun salutations, Paprika will be sketching moody landscapes, and Cinnamon will be practicing its vocal scales, ready for its next grand entrance into a dessert. The sheer amount of ego packed into these tiny jars is truly astounding. And don’t even get them started on the concept of “best before” dates – they consider them mere suggestions,

Chapter 3: The Underdogs and the Wannabes: Salt, Pepper, Garlic, and the Hot Sauce Renegade (Approx. 290 words)

Beyond the A-listers, we have the workhorses, the unsung heroes, and the occasional imposter.

Salt: Salt, bless its crystalline heart, is the oldest and wisest of them all. It’s seen everything. It knows its fundamental importance but struggles with an existential crisis: “Am I a spice, or merely a mineral?” it ponders deeply, late at night, shimmering under the pantry light. It’s often overshadowed but knows that without it, all other flavors are meaningless. Its main complaint? People under-seasoning. “They don’t understand my complex mineral structure!” it laments, feeling unappreciated. “They just want me to… well, be salty.”

Black Pepper: Black Pepper is Salt’s trusty, slightly aggressive sidekick. Always there, always reliable, but a little bit prickly. It despises those pre-ground versions that sit stale in the shaker. “Freshly cracked, or nothing!” it barks, convinced that anything else is a betrayal of its peppery essence. It fancies itself a connoisseur of heat, constantly comparing notes with its spicier cousins.

Garlic Powder: Garlic Powder is the reliable, slightly unglamorous friend. It’s not as flashy as fresh garlic, but it’s always there in a pinch. It quietly shoulders the burden of convenience, often feeling overlooked. Its dream? To be recognized as an essential building block, not just a shortcut. “I want to be loved,” it sighs, “maybe ward off vampires, even if I’m dried.”

The Hot Sauce Bottle (An Uninvited Guest): Then there’s the rogue element: the Hot Sauce bottle. It’s not technically a spice, but it insists on hanging around the spice rack, making demands. “We demand recognition! We demand bottles! Seriously? Just condiments?!” it screams through a tiny megaphone, stirring up revolutionary fervor among the other chilies. The other spices mostly ignore it, finding its antics a bit uncouth, though the chili flakes secretly admire its fiery bravado. They all agree it really belongs in the fridge, but who’s going to tell it?

The spice rack, my friends, is not merely a collection of powders and seeds. It’s a bustling metropolis of personalities, each one adding a unique flavor to the grand comedy of your kitchen. So next time you reach for that jar, take a moment. You might just hear a tiny, dramatic whisper from within.

https://frogsaga.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=518&action=edit

https://spicesinc.com/spices/a-z?srsltid=AfmBOop9o1oRfXBUigdOJwo73-UpZA3UnN2dxzpNhBpr5ncQmFVXio0c

https://www.masterclass.com/articles/a-list-of-the-27-essential-cooking-spices-you-need-to-know