Sichuan pepper, also known as huājiāo (花椒) or málà pepper, is not simply another hot spice—it’s a sensory adventure. With its citrusy aroma and uniquely tingling, numbing sensation, this spice from Southwest China has captured the imagination of chefs, food historians, and home cooks around the globe. But what makes it so special, and how has it traveled from mountain ridges to global spice racks? Today, we delve into the vibrant world of Sichuan pepper to explore its flavors, varieties, culinary applications, and its rich cultural history.

What is Sichuan Pepper? More than just a peppercorn.

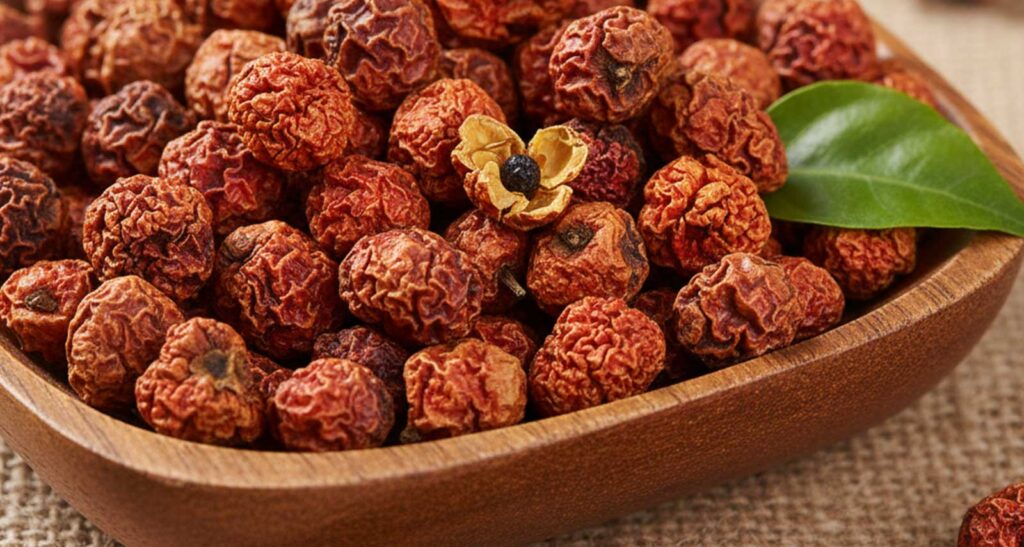

Though its name suggests a kinship with black pepper or chili, Sichuan pepper comes from an entirely different botanical family. It is the dried outer husk (pericarp) of a berry from plants in the genus Zanthoxylum, part of the citrus family, Rutaceae—not related to true peppers.

The defining characteristic of Sichuan pepper is its numbing‑tingling effect, caused by a compound called hydroxy-α-sanshool. This molecule activates the trigeminal nerve, making your lips and tongue feel like they’re vibrating gently—akin to the sensation of carbonated pop or a soft electrical hum.

Varieties and regional types

Major species

There are several species of Zanthoxylum used to produce Sichuan peppercorns, each offering distinct flavors and properties:

- Zanthoxylum bungeanum: Perhaps the most widely used, this “red” variety has reddish-brown husks, a warm citrus-woody aroma, and a moderate-to-strong numbing intensity.

- Zanthoxylum schinifolium: Often referred to as “green” Sichuan pepper, these bright green husks are harvested earlier, producing a fresher lemony citrus scent and a sharper, quicker numbing effect.

- Zanthoxylum armatum: Found widely across the Himalayan region (Nepal, Bhutan, parts of India), this variety often delivers floral-fruity aromas and a potent, lingering buzz when dried.

Notable regional variants

Beyond the typical red and green, there are more specialized or regional cultivars:

- Hanyuan peppercorn: Grown in Hanyuan County (Sichuan), sometimes dubbed the “Rolls-Royce” of Sichuan peppers for its unmatched fragrance and long numbing sensation.

- Wild mountain varieties: Found in remote, mountainous zones, wild Sichuan peppercorns often come with more nuanced aromatics, giving high-end chefs a prized specialty.

Culinary uses

Sichuan pepper is deeply woven into the tapestry of regional cuisines, especially Sichuan cuisine, but its influence reaches far beyond.

In traditional Chinese cooking

- Málà (麻辣): This iconic flavor profile combines the numbing of Sichuan pepper with fiery chili heat. It forms the backbone of dishes like Chongqing hot pot and mapo tofu.

- Five-spice powder: Whole or ground Sichuan pepper is a key ingredient alongside star anise, cassia, fennel, and cloves.

- Pepper oil and salt: You will often find huājiāo yóu (pepper-infused oil) or huājiāo yán (Sichuan pepper salt), made by toasting the husks with salt—used as dipping sauces, seasonings for meat, or even sprinkled on snacks.

- Leaves: The fresh leaves of the pepper tree are sometimes used in soups or fried with vegetables.

Global and modern takes

- Stir-fries and grilled meats: It’s common in stir‑fried dishes or grilled fish to toast the peppercorns, blooming their aroma just before serving.

- Pastries and ice cream: Because of its citrus and floral notes, Sichuan pepper is even used in desserts—perhaps surprisingly in pepper-salted butter cookies or as a zingy topping for ice cream.

A spice with history: trade, tradition and culture

Origins and trades routes

Sichuan pepper has been used in China for centuries. While local to Sichuan and its mountainous neighbors, its appeal grew beyond regional cuisine. As spice routes expanded, huājiāo traveled via internal trade within China and eventually reached the Himalayas, Nepal, and India, becoming part of local Himalayan cookery.

China’s historical trade networks—both land (like portions of the Tea Horse Road) and river routes—facilitated the movement of Sichuan pepper. It morphed into both culinary and medicinal goods, contributing to the broader exchange of spices throughout Asia.

Cultural significance

- In Chinese rituals: In some regions, Sichuan pepper was more than a spice—it carried symbolic weight. Certain varieties were considered tribute spices, offered to nobility for fertility or well-being (as noted in historical accounts).

- Traditional Chinese medicine: Huājiāo is believed to have warming properties: used in traditional Chinese medicine to improve circulation, relieve cold sensations, and stimulate digestion.

- Modern revival: With the global interest in Sichuan cuisine, this pepper has become an ambassador of Chinese culinary heritage—used in modern fusion dishes, specialty oils, and even trendy snacks.

Health and wellness

Sichuan pepper is more than just culinary flair. According to both traditional medicine and modern research, it offers some notable benefits:

- Circulation and “warming” effect: The essential oils (like limonene) in the pepper can stimulate peripheral blood flow—a reason it’s used to treat “cold hands and feet” in traditional Chinese medicine.

- Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory: Some studies show that extracts from Sichuan pepper have antibacterial properties against common pathogens and may reduce inflammation.

- Immune support: Rich in vitamins A, C, E, and minerals (zinc, potassium), it’s thought to “expel wind and dampness,” supporting the body’s defense against illness.

- Mood and sensory stimulation: The tingling sensation itself may release endorphins, giving an uplifting, “awake” feel.

The science behind the tingle

What makes your tongue feel like it’s buzzing? The science lies in hydroxy-α-sanshool, the compound in Sichuan pepper that stimulates tactile sensory neurons without triggering traditional “taste” receptors.

A study even measured the frequency of the vibration sensation at around 50 Hz, similar to the hum of an electrical current. This is not a burning heat like capsaicin (from chili peppers), but more like a gentle buzzing or fizzing — the hallmark of málà.

Taken together, it all reveals that Sichuan pepper is a spice that transcends mere seasoning: it’s a cultural symbol, a historical traveler, a culinary technique, and a sensory phenomenon. From the red peppercorns that power Sichuan hot pots to the delicate floral whisper of its green variety, its footprint is both vast and nuanced.

Whether you’re a curious cook wanting to try your hand at mapo tofu, a spice aficionado intrigued by the science of that tingle, or someone captivated by the global journey of ancient ingredients, Sichuan pepper offers endless depths.

Try it, share your favorite ways to use it, and let the buzz of huājiāo awaken your culinary imagination.

Leave a Reply